Romance Novels, Racism & Restorative Justice part 2: how to write about communities you’re not part of with respect

Would you center an exploration of slavery on the life of this woman?

Many of you may have read my previous post in which white historical romance author Stephanie Dray joked on Facebook about a 50 Shades of Grey BDSM mashup novel with Thomas Jefferson & Sally Hemings. Although the FB screen cap says of the book “it’s happening, people” she denies that such a book was ever planned.

What she doesn’t deny is that she also engages with the theme of slavery via her book on Jefferson’s daughter, Patsy. But here’s the challenge:

Dray describes it as “a mainstream historical fiction book about Thomas Jefferson’s daughter Patsy” and says, “It has been my ambition, from start to finish with this project, to shed light on the devastation of slavery–a devastation that became more and more evident as we researched.”

And yet, these challenges and complexities aren’t central to the book. Here’s the general description:

“America’s First Daughter is a straight historical fiction that offers a sweeping treatment of Martha ‘Patsy’ Jefferson Randolph’s life from dutiful daughter traveling at her diplomat father’s side to First Lady during her father’s presidency to mistress of the iconic Monticello.” So this is a story of a white woman coming into her own. And slavery is so far in the background that it doesn’t get a mention. Maybe it’s part of the “sweeping treatment.”

As a number of other women of color and white allies have pointed out on twitter and elsewhere,

https://twitter.com/AyadeLeon/status/581451365173497857

this is exactly the problem. Racism is about brown folk’s lives always being in service to white peoples’ lives. Dray really thinks she’s dealing with slavery in some meaningful way because she chose to write a story that centers on a white woman who was affected by it. But however much Patsy may have had to deal with some discomfort about slavery, mostly her life was enriched by it. Namely, the “iconic Monticello” that she became “mistress” of was built and maintained by slave labor. While Dray and her partner express outrage towards slavery, their very fascination with the wealthy white families of the time expose their simultaneous attraction towards the institution and the white wealth and power it enabled. Patsy never chose to free any enslaved Africans, she sold them to save herself financially.

There are ways for white people to combat racism by writing about white people. Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible is a great example. However, in historical fiction that includes real historical characters, one would have to choose more wisely than this Patsy.

Here’s a question: what about the women abolitionists at the time? What are the stories of the women in abolitionist John Brown’s life or the wives and partners of those involved in the raid on Harper’s Ferry (a white man who attempted to start a slave revolt)? I will remix Audre Lorde for the occasion: The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. And the master’s family’s stories will never do justice to the people they “owned.”

Dray says she wants to “make clear that the scars of that devastation are still evident today in our politics and our culture.” Unfortunately, she’s made clear that the scars are still in her attitude and in her book.

I don’t want to say here that people should not write about targeted communities they aren’t part of. Neither am I advocating censorship, nor self-censorship. But if you don’t want to be accused of racism or appropriation (or worse yet, find yourself guilty of it), then check your motives and proceed with caution. Daniel Jose Older has some GREAT tips in his article “12 Fundamentals Of Writing ‘The Other’….How to respectfully write from the perspective of characters that aren’t you.”

And here’s my experience:

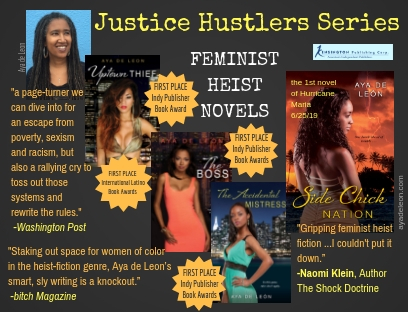

I write about women of color from low income backgrounds (which in some ways describes me and definitely describes much of my family). I also write about sex workers in New York, which is fully outside of my experience and of those close to me.

I chose sex work very specifically, because I wanted to write about sex and center my work in a location that was inherently political. Sex work is about class, gender, bodies, sexuality, commerce, race, nation, culture, technology, and more. Everything that matters to me. But there are all these highfalutin ideas, and then there are actual people actually doing the work and actually getting targeted with the oppression or facing the threat of dire consequences in their work every day. The book wasn’t going to be in integrity unless I developed strong reciprocal connections with people in the sex work communities.

I chose sex work very specifically, because I wanted to write about sex and center my work in a location that was inherently political. Sex work is about class, gender, bodies, sexuality, commerce, race, nation, culture, technology, and more. Everything that matters to me. But there are all these highfalutin ideas, and then there are actual people actually doing the work and actually getting targeted with the oppression or facing the threat of dire consequences in their work every day. The book wasn’t going to be in integrity unless I developed strong reciprocal connections with people in the sex work communities.

So I have built relationships with people fighting for justice for sex workers to make sure that my book isn’t just a fantasy of what sex workers might want, but actually checking with them. Some folks were glad to talk to me for free, and in other cases, out of respect, I hired sex worker experts to consult and paid their going rate for their time. Dray will never know what Sally Hemings was thinking or feeling, but she can certainly check in with women of color writers, and consult with them in ways that compensate them fairly.

But as a person of privilege, if you “believe strongly” in a particular cause where you are not part of the group being targeted, the Ally 101 role is to listen to the people from that group and accept the expertise of people who are leaders in that movement.

I started by reading $pread Magazine, a sex worker industry publication that has since folded. Then I had a friend read it who is a sex worker. She enjoyed it, but she didn’t have a perspective on the larger industry beyond her type of work. So I reached out to a sex worker activist who offered to read my book. She didn’t want to be paid, as she considered it part of her activism. We had several lunches where I picked up the tab, and then she read my 3rd draft. And she ripped it to shreds in several places where I’d gotten things wrong.

There were little things: she told me I needed to change some of the character names. I had stripper names for some of the women who were selling sex; in that part of the industry the names were different. My sex worker characters were also underchanrging for various services. These were easy to change, but some of the things were not. For example, she objected to the fact that, in an earlier draft, the sex workers were robbing their clients. She said this is a terrible stereotype that all sex workers are thieves and that they hate their clients and want to take advantage of them. Bam! Right there, she eviscerated my entire plot. But guess what? I came up with something better, something that not only supported her request, but also managed to reinforce another important issue in the sex work community. Currently, there are a lot of campaigns against selling sex, based on situations where people (mostly women and girls) are being trafficked against their will. Trafficking is a huge problem, but most of these approaches that conflate commercial sex, sex work, and trafficking, are less effective with trafficking and also directly harm sex workers.

When I wasn’t able to have the sex workers robbing their clients, I developed the idea that they came across a group of crooked CEOs who were involved in a sex trafficking scandal. I changed the plot so that my protagonist’s team robs these CEOs to keep their clinic open, and sending some of the money to organizations that work directly with the women who’ve been trafficked. So now the book is on message with what sex worker activists are saying consistently as part of their real-world fights: sex workers care about trafficking and don’t want sex work and trafficking to be conflated. As a work of fiction, it’s able to go a step further and have sex workers who are part of solutions to trafficking, by redistributing wealth earned by traffickers, getting money back to women trafficked, and the story also exposes some of the hypocrisy in the anti-trafficking movement. When a person builds deep alliances with folks from the community they’re writing about, they deepen the work and can further align the work with the movements of folks from that community that are fighting for the human rights they need and deserve.

Back to Dray, if she really does care about racial justice, then she probably needs a new approach. Attention all writers: writing about a social justice topic (like race or gender or sexuality or sex work or class) doesn’t automatically make you part of the solution. And it’s particularly dicey when what you’re creating is a product to be sold. I have written a bunch of books that didn’t include sex workers. But I had trouble selling them. So when I realized I would need to write something sexier, I decided to write about sex work, because it’s so political. And I hope my book does well. And I hope to get paid, for the thousands of hours I put into it. However, I have worked hard to align the impact and message of my book with the needs of the sex worker’s community. And if I just included sex worker characters without aligning the book with the movement goals of real sex workers, it would be appropriation. As Audre Lorde put it, use without the consent of the person being used is abuse. Now, not every sex worker is going to agree with me, and some will say I’m exploiting or appropriating anyway. And when those criticisms come, I get to take another look at myself, and see where I can do better. But going in, I know that built real relationships, and put in lots of time to educate myself, and am in community and communication with a number of badass sex worker activists who will kick my ass if my work is potentially hurting their movement. And beyond that, I can see that it’s not some charity work to help sex workers–the targeting of sex workers is part of the targeting of women in general, and women of color and low income women in particular. So human rights for sex workers moved all of humanity forward. And the biggest green light I’ve gotten is all the sex workers who are telling me yes, write and sell this book, we want these stories out there!

As with any job, there are similarities and differences between different workers’ experiences, and a range of attitudes towards the work

To that end, I feel good about the range of experiences in sex work that I’ve portrayed, from horrible and coercive to the best choice a trauma survivor could make in a terrible situation, to having fun and making great money. And I feel good knowing that whatever the response to my work, I have shaped my vision in contrast to the tired and damaging tropes of sex worker victim and sex worker villain. My protagonist is a sex worker hero. Flawed and imperfect and a total badass. Her lives and her struggles are in the center of the book.

Part of the problem for Stephanie Dray in writing about slavery in the context of a white woman’s heartwarming journey of coming into her own is this: slavery wasn’t heartwarming. Decidedly not for the enslaved Africans. So you can’t really fit a story of a black woman in that era into the women’s fiction formula, because there is no happy ending, no coming into her own. Slavery was all about being owned, and the ripping apart of human bonds between black people. Between romantic partners, between parents and children. Everyone. And if you tell a touching story about white people with slavery as a backdrop, that’s working at a sort of cross-purposes, because on the one hand, you say you want racial equality, but your book puts white people in the center and black people as the backdrop. Perhaps the fight for racial equality won’t be fought or won on the pages of antebellum historical novels written by white women about a white woman. Perhaps if Dray really cares about racial equality, she can act powerfully in the present and support the voices of black women and women of color in her genre.

Please note, I am having trouble pulling up all the past tweets about it from earlier this month. If I missed you, please forgive me. If you wrote or spoke about the situation at the time, or would like to now, get at me on twitter @ayadeleon & I will include in future posts in the series. Thanks!

Great blog post. And you’re right, she could have written about white abolitionists like Angelina Grimke and her sister who educated their black nephews.

Pingback: Celebrating #TransDayOfVisibility: Meet My Character Serena | Aya de Leon

“…came across a group of crooked CEOs who were involved in a sex trafficking scandal…” Sounds like something I’d like to read. When/where can I buy it?